Introducing #postmarketOS-lowlevel

But before we get started, please keep in mind that these are moon shots. So while there is some little progress, it's mostly about letting fellow hackers know what we've tried and what we're up to, in the hopes of attracting more interested talent to our cause. After all, our philosophy is to keep the community informed and engaged during the development phase!

For those new to postmarketOS, we are a group of developers, hackers, and hobbyists who have come together with a common goal of giving a ten year life cycle to mobile phones. This is accomplished by using a simple and sustainable architecture borrowed from typical Linux distributions, instead of using Android's build system. The project is at an early stage and isn't useful for most people at this point. Check out the newly-updated front page for more information, the previous blog post for recent achievements, and the closed pull requests to be informed about what's going on up to the current minute.

Let's dive in!

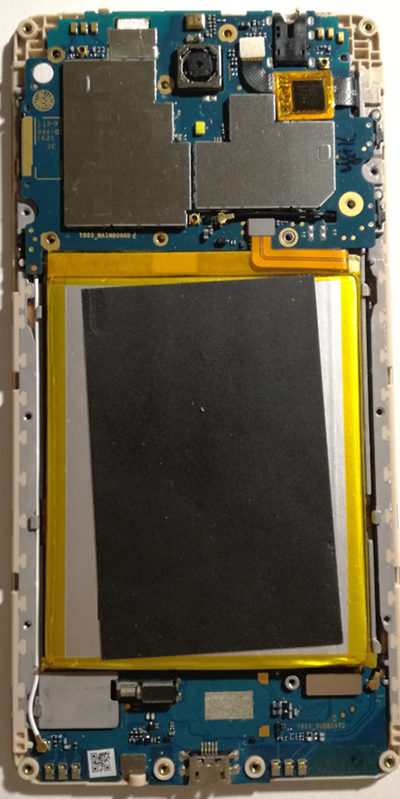

Open Bootloader for MT6735P

Just like most Android phones, the bootloader of this particular device is based on LK (Little Kernel). In fact the source code for LK is available under the MIT license and just about every smartphone implementing the fastboot protocol has some kind of LK installed. The downside to this license is that it also allows the vendor to create a fork of the bootloader without giving the customers the changed source code, and unfortunately it is common practice for vendors to make use of this right.

However, @McBitter is not interested in this messy workaround. He would rather eliminate the need to run this closed source blob altogether and make the upstream LK code run on the MT6735P! This approach gives us an elegant solution for incrementally porting LK to other MediaTek SoCs by reusing the same shared LK source code in the process! Why go through this trouble for an seemingly obscure device? Consider this Wikipedia article for devices based on MediaTek SoCs, detailing a wide range of manufacturers using these chips besides Coolpad. Just to name a few:

- hTC

- Huawei

- Lenovo

- LG

- Moto

- Sony

The best part is that all the information collected in the process of porting upstream LK also contributes a significant step towards booting mainline Linux on these devices.

Serial Access Without Hardware Modification?

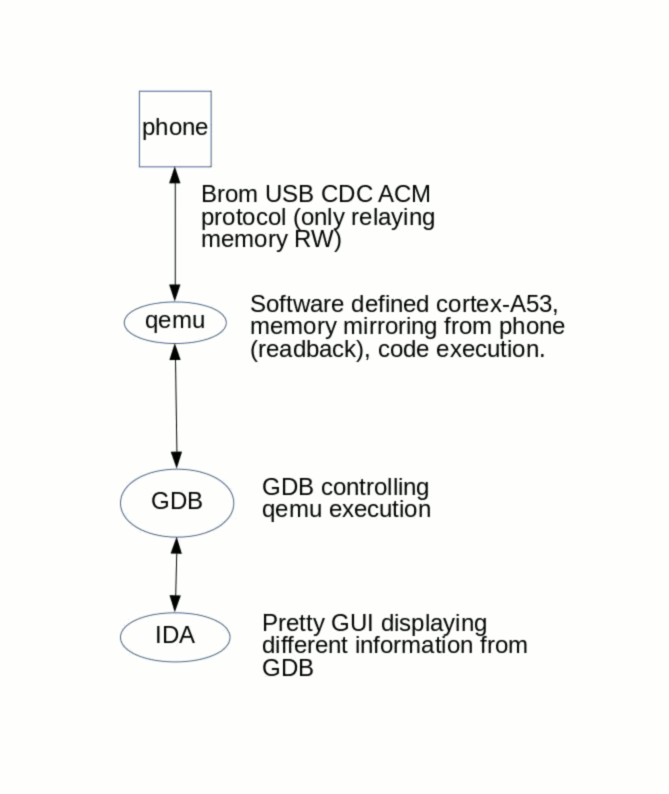

While it would be possible to connect a serial cable to the USB port of many MediaTek devices, @McBitter and @unrznbl had a different concept that would turn it up to eleven.

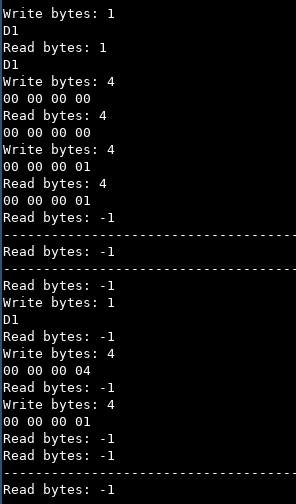

Instrumentation With QEMU?

-1 instead of the requested amount of bytes to read.The memory restrictions would make debugging with QEMU impossible.

DRAM Calibration Data Obtained!

The months rolled by with many new theories being tested without, unfortunately, having even the tiniest bit of success. After taking a break for a few weeks, @McBitter changed his focus to the earliest piece of code of the boot process that can be modified, which is the preloader. The preloader is loaded by the BROM (boot read-only memory), which in turn loads LK.

The BROM is only able to initialize the SRAM (static random-access memory), which is very small and expensive (but fast, it gets used for CPU caches as well). In contrast, the "real" RAM (in the order of gigabytes nowadays) most of us may be familiar with is the cheaper DRAM (dynamic random-access memory). Initializing the DRAM is the most complex task the preloader has to do before passing control to LK. To make it work, the preloader must use some kind of calibration data for configuration, and there is so much of this calibration data that it's far easier to extract it from existing firmware than write it from scratch.

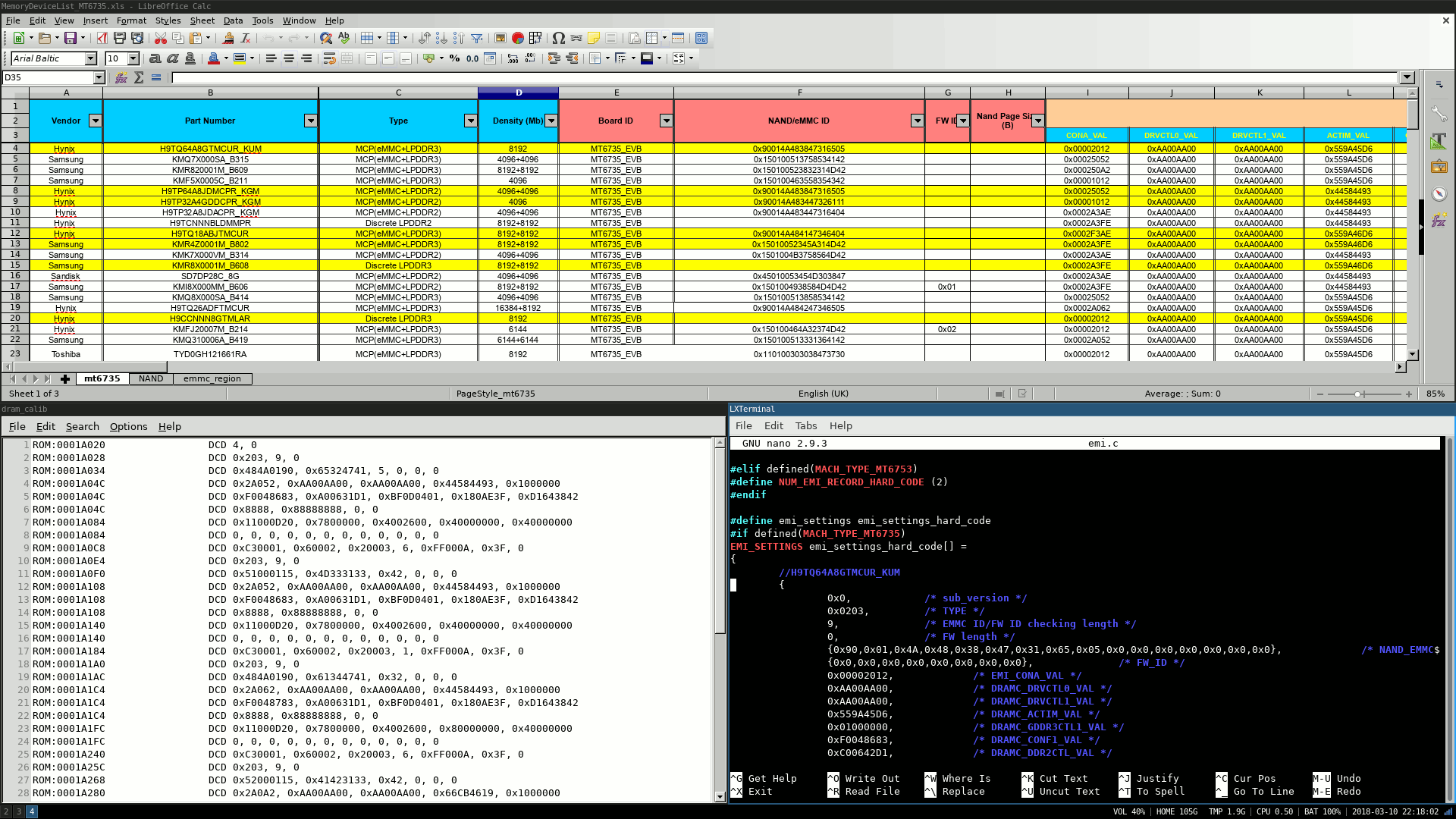

Here's the catch: it is hard to find the calibration data in the compiled firmware blob, as it is unclear where exactly it is stored and which format it has. @McBitter helped himself to an older source code leak of another MediaTek SoC: he found the calibration data in there, but it was not a complete match for his particular SoC. It did, however, serve to clue him in on how the structure looked! Since his success hinged more on luck than anything else, he selected a random pattern (0xAA00AA0) from the C struct with the calibration data in the source, and searched for it in the binary blob: "After running the search we immediately got a result and it seemed obvious that we've hit the jackpot on this one!"

You can find the extracted DRAM calibration data here, and the screenshot shows it in a spreadsheet.

Open Baseband Firmware for MT6260

Why Is Proprietary Cellular Firmware a Problem Again?

Having the main processor of a phone running a secure operating system would already be a great achievement in today's mobile world. We believe that starts with running official kernel releases on these devices, instead of unofficial and outdated forks where no one can realistically keep up with security patches.

However we must not forget about the peripherals inside the device, which run their own firmware. Oftentimes they are able to compromise the whole system, and they are "of dubious quality, poorly understood, entirely proprietary, and wholly insecure by design".

One way to deal with these is implementing kill-switches and sandboxing the cellular modem, an approach currently being planned for in the Librem 5 and Neo900. This allows you to be in control of the device by turning the modems off, despite the fact that you don't know what they are doing while they are on. Another approach is analyzing and binary patching the existing firmware files.

But let's be honest here, isn't it outrageous that even the projects coming from people who value free and open source software, security and privacy, need to work around this gaping security hole present in nearly every phone ever made? Yes it is a daunting task to truly fix this with an open source implementation and it will take forever. But we have to start somewhere, and letting more time pass by won't help either!

Porting OsmocomBB to Fernvale

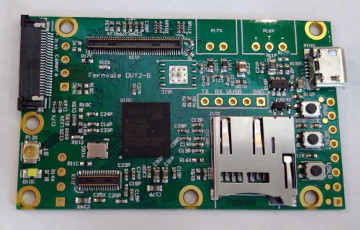

In search of an alternative, @unrznbl chose the Fernvale platform as new target. There's a nice introduction talk by its creators that explains how Fernvale was created to enable open source engineers to build phones and other small devices with the cheap MT6260 SoC.

Blinking LED

Afterwards he continued to replace the functions in the layer one firmware in OsmocomBB with stubs that work on Fernvale to see if he can get more of OsmocomBB running. But he found out that the configuration in his linker script didn't provide enough space for the compiled firmware.

In order to gain more space, he is looking into using more of Fernvale's software stack: their preloader usb-loader.S in combination with fernly-usb-loader.c should be able to load both Fernly (to initialize the large DRAM) and then OsmocomBB from a connected PC via USB. The workflow is somewhat similar to using fastboot boot (or pmbootstrap flasher boot) to run a kernel and initramfs coming from the PC.

Utopic Vision

After the entire layer one firmware of OsmocomBB is ported to Fernvale, it would be possible to do 2G voice calls, send SMS and access the Internet from a laptop via tethering (just like it is possible with old Motorola phones today). @unrznbl is also involved in creating layer one as a library for use in NuttX, bringing full userspace phone functionality to it. With this, in combination with an oFono or RILD compatible interface added to the code, postmarketOS and friends (yes, even Android based systems like LineageOS), would be able to talk to the cellular modem inside the phone. All without the rather inconvenient Laptop in between.

This same effort can also benefit the newer MediaTek SoCs, such as the MT6735P (which @McBitter is experimenting with). Ultimately we, and likely lots of free software hackers, are dreaming of libre support for GSM protocols greater than 2G (3G, 4G, LTE and so on).

Let's Do Something!

If you're like us, you don't want to live in a world where everyone is carrying around phones that can be hacked up remotely by anyone with enough money or motivation. Regardless of the OS the phones are running: when we want the people to be in control of their own devices, these must be running FLOSS down to the firmware level. That is the only right way to enable the community to patch security holes after the vendors abandon their software. Every complex piece of software has security bugs!

How?

- Hack along in #postmarketOS-lowlevel if you feel like you're up to it or want to get there (IRC/Matrix).

- Help out at Osmocom/OsmocomBB (IRC). The latter is the base rock for free software cellular modem firmware, but they are hopelessly underpowered right now. Even if you can't contribute with code, you can ask for other ways to help out!

- Contribute to postmarketOS: Check out the How Can You Help? section from the last post.

- Raise awareness about problems with proprietary firmware (e.g. by sharing this article to fellow hackers).